- Home

- Sharyn McCrumb

The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel Page 8

The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel Read online

Page 8

I suppose I could have wrangled a desk job for myself if I had tried. My Harriette would have been overjoyed had I done so, but I wasn’t much past thirty, and I had no desire to sit at a desk in Raleigh, firing paper salvos and dodging requisition forms while the War whirled on without me. That was in 1861—early days. We were all fools back then.

They assigned us to the 14th Regiment of North Carolina to begin with, and by the middle of June we had settled in at Camp Bragg, some two and a half miles from the town of Suffolk, Virginia. Twenty-six miles away, in Newport News, the enemy had landed a large force, and, since Camp Bragg straddled the junction of two railroad lines (the Petersburg & Norfolk and the Roanoke & Seaboard), we thought ourselves in some danger of attack. Every night pickets were posted a mile and a half from camp, and the rest of us slept with our weapons at hand. The battle passed us by, though, that time, in favor of another railroad town: Manassas Junction, in proximity to Washington.

A few weeks after that, the government mustered new regiments, some of them comprising troops from the mountain counties. I was gratified, but not entirely surprised, to receive a letter from the Adjutant General of North Carolina’s troops, saying that I had been elected colonel of the 26th Regiment, and would I accept the commission?

I delayed just long enough to transfer my old command to another Asheville lawyer, Philetus Roberts, and then I hightailed it down to Raleigh, where I wasted some time trying to persuade the bureaucrats to transfer my original troops, the Rough & Ready Guards, to my newly formed regiment. They thought not, of course, so I had to leave my boys in the 14th, and, after a few weeks’ leave at home, I made my way over to Camp Burgwyn, on the Atlantic coast near Morehead City, where we whiled away the waning days of summer watching Yankee sailing ships cruising past, without bothering to waste a shell on our fortifications.

I chafed at the idleness of waiting for the War to find me. I declined an offer to run for the Confederate congress, because I had been so loath to leave the Union in the first place. Then I proposed to go on a recruiting trip back to the mountains to garner more troops, but my deliverance from that seaside monotony came from another quarter: in February 1862, I was ordered to take my regiment to New Bern, where on March 14, the Union forces, under General Ambrose Burnside, attacked.

Was James Melton there in the swamp with us?

If he was an enlisted man, I would have no way of remembering him, but I’ll wager that we’d have the same nightmares about that day. My regiment was stationed on the right wing, caught between the woods, through which enemy forces were advancing, and a swamp.

About midday we fell back, the last Confederate troops to retreat. When we got within sight of the River Trent, I saw that the railroad bridge was in flames. The other regiments, having made good their escape, had fired the bridge after them—leaving us trapped.

The river itself was impassable, but, fortunately, I knew something of the terrain thereabouts, so I led my men to nearby Briers Creek, seventy-five yards wide and too deep to wade, but it was our only hope of escape. The only boat to be had was a wooden boat that would hold three men at a time—and we had hundreds of soldiers to ferry across the water.

With the enemy less than a mile away and closing, I spurred my horse into the creek, but midway across he refused to carry me further, and so I was forced to swim for it. One of my men brought the horse ashore, and there I mounted him again, and, accompanied by some of my officers, I rode to the nearest house, where we commandeered three more small boats to effect the evacuation of my troops.

We had to carry the boats back to the creek on our shoulders, and then, amidst shell fire, and clouds of acrid smoke, we set back across the water to rescue the soldiers, a handful at a time. It took all of four hours to get my regiment translated to safety on the other side of Briers Creek, but, except for three poor fellows who were drowned, and those who fell in the redans holding off the enemy, we got the soldiers across.

That was my baptism by fire, and, while I hope I acquitted myself well and did my best for my men, the futility and haphazardness of war were impressed upon me.

The commanding officer in the Battle of New Bern had been my fellow congressman Lawrence Branch. He had taken the rank of colonel about the same time I did, but he had recently been promoted to Brigadier General, though I cannot say I was impressed with his performance in that position. I thought I could do at least as well, and so shortly after the battle, I set about trying to raise a legion—that is: to add twenty additional companies to the ten I already had, plus a complement of cavalry and artillery. If I could amass that number of troops willing to serve under me, I would be promoted to Brigadier General as well.

This venture went nowhere, for shortly after I began my campaign, the Adjutant General informed me that the newly passed Conscription Act had furnished enough soldiers to meet the quota for North Carolina. I am not a lawyer for nothing, though, and I spent a few more weeks trying to find a loophole in the recruiting laws, and thinking up ways to raise my legion in spite of the bureaucrats’ efforts to thwart me. It was like trying to swim in molasses. No sooner would I enlist recruits than the generals would assign those men to other people’s commands. I could see that they meant to keep me a colonel in perpetuity, so I abandoned the idea of trying to work in the military hierarchy, in favor of going back to the game I could actually play: politics.

The election for governor was coming in August, and the Raleigh Standard newspaper was endorsing my candidacy—if I should choose to run. Why, I’d have run for the governorship of purgatory, if the alternative was being outranked by the likes of General Branch and suffering the whims of pettifogging bureaucrats. I had one ace in my hand in this venture: my opponent was not in the military, and soldiers could vote.

The election was not until August, though, and meanwhile I had to soldier on as colonel of the 26th North Carolina, and try to remember that the enemy was the Union army, and not those graven fools in the government back home.

June found me back in Virginia, to join my regiment to Ransom’s Brigade for the Seven Days Battle. The Union forces, under the command of General George B. McClellan, had landed on the Virginia peninsula, with the intention of advancing west and taking Richmond. When you are well below the exalted rank of general, you have very little idea what is going on in the campaign, even if you are in the forefront of the fighting. Seen up close, war is all noise and smoke, shouting men, and belching cannons, and through it all the stench of blood and gunpowder. There may have been some grand design conceived by General Lee and his advisors, but it wasn’t apparent to those of us in the thick of it. Orders failed to reach the commanders. Reinforcements did not arrive. The fighting seemed sporadic and uncoordinated.

The War was prolonged mainly by the fact that General McClellan was just as bewildered as the rest of us. He didn’t seem to know that his army outnumbered the Confederate forces two to one. He didn’t realize that he was closer to Richmond than the defending army was. And he hadn’t grasped the fact that he was winning.

Instead of pushing on to Richmond and to victory, he pulled his troops back to the James River, planning to load them back on the ships they came in and sail away to safety. We should have given him a parade, but instead we chased him on his way, and at the last piece of high ground before the river, he decided to stand and make a fight of it—at a place called Malvern Hill.

He lined up his artillery on the top of that hill, and he stationed his infantry forces at the ready to engage us in the intervals between bursts of cannon fire.

Our orders were to take that hill.

If I had occasion to meet James Melton, we would not slap each other on the back and reminisce about Malvern Hill. It had none of the golden glory that Shakespeare attributed to Agincourt. It had all the filth and squalor of a hog-killing.

Our orders were to charge that hill and take out McClellan’s cannons. To that end, soldiers would charge across the open field, trying to ascend the slope, and a whistling shell

would spiral down and blow them to pieces as they ran.

If I am remembered at all for my part in that sorry spectacle, it is for a jest I made in hopes of boosting the morale of my poor beleaguered men. Once when we were pinned down in a hail of bullets, a startled rabbit jumped out of the nearby underbrush and streaked across the field. Seeing this, I shouted, “Run, you sorry rabbit! If I wasn’t the governor of North Carolina, I’d run, too!”

Well, I was two months shy of getting elected, but at least I stood my ground at Malvern Hill, and when the time came to cast the ballots, the troops remembered me favorably, so that I won the election by a margin of two to one.

In September I headed back to North Carolina on furlough, for I would take the oath of office before a judge in mid-September. The 26th North Carolina fought on without me, at Antietam Creek in western Maryland, where they say the very air turned red from all the blood shed in that terrible battle. By the end of the fighting, the dead lay stacked like cordwood, a dozen feet deep in the roadbed. General Lee lost a quarter of his army in that one battle, and with it all hope of foreign alliances that might have equipped us to withstand the onslaught of the Union forces.

I was gone from the army for good before Antietam, ensconced in the Governor’s Palace in Raleigh, where the battles were fought with forms, and requisitions, and letters couched in diplomatic insolence.

But James Melton had no such escape. He would have staggered on in rags and tattered boots, living on hardtack and homesickness, until the bitter end—which came for him in a Union prison camp many miles from home.

No, I would not reminisce about the War with this veteran of the 26th North Carolina. There was nothing either of us wanted to remember.

PAULINE FOSTER

March 1866

March finally wore out, and the fields got green again, but all that meant to me was that I’d be working in the fields as well as doing all the household chores. It made it easier to walk the mile or so to a neighbor’s place to visit a spell, when I wasn’t too tired of an evening to manage it. My fever never did come back, though, and that rash I’d had when I came here had faded away altogether, so I began to think that Dr. Carter’s bluestone cure had done its work. He said I had to keep going to see him, though. Some ailments, he said, were like flies in winter—just because you didn’t see any around didn’t mean they were gone for good.

“I don’t think you are well, Pauline,” he told me, when he gave me my latest dose of medicine. “And I think you might still be able to pass this disease to someone else if you were intimate with him.”

“Oh, I’ll be careful,” I told him. I meant I’d take care in deciding who it was I wanted to infect. Sometimes I felt like that angel with the flaming sword that drove Adam and Eve out of Eden: I had a God-sent weapon that would bring death to ever who I chose.

* * *

“We have not seen so much of Tom Dula lately,” I said to Ann one afternoon. I had spent all day planting corn in the field with James Melton, and when I got in, stiff-backed and bone-weary, Ann had told me to wash her bed sheets before I started on supper. I couldn’t refuse for fear of losing my situation, but I figured I owed her a little pain in return, so while I was making biscuits to go with the stew, I made that remark about Tom, as innocent I could make it sound, knowing it would be salt in her wound, and glad of it.

Ann stiffened for a moment, but then she made her voice light, and she said, “Well, it’s planting time. Everybody around here has plenty to do right now.”

I snickered. “Reckon he’s planting something, all right. Over at Wilson Foster’s.”

Ann slapped me hard, leaving a white handprint on my cheek from the flour. I just smiled at her and went back to kneading the biscuit dough. She wiped her hands on her skirt, but she just kept standing there. Her nose got red, and I saw one solitary tear leak out of the corner of her eye and slide down her cheek.

Finally she said, “He don’t care nothing about Laura Foster.”

“Well, in case his mama ever dies, I reckon he’ll need somebody to look after him. He might be giving some thought to that. Besides, a marriage seldom comes about on account of what a man wants. If I was you, Ann, I’d be studying about what Laura wants.”

Ann picked up a ball of dough and began to roll it around in her hand. Then she squashed it flat on the flour cloth and pressed down hard with her palm. “It ain’t like he has anything to offer anybody,” she said.

“I couldn’t say,” I said, taking care to keep my voice light and indifferent. “But her mother is dead, leaving a passel of children and Wilson Foster himself needing to be looked after. No love lost between Laura and her father, from what I hear. Now if it was me, I reckon I’d take just about any opportunity to get shut of all those young’uns and an ornery father who used me as a house servant. Did you not find yourself in that self-same situation when you were fifteen?”

She gave me a stricken look then, and I knew I had hit the mark. Ann had married James Melton to get away from a fractious parent and a home life of toil. She must have known as well as I did that Tom Dula was a deal more appealing to a young girl than old sobersides Melton had ever been. Maybe Laura Foster had precious little to gain by marrying Tom Dula, but what did she have to lose?

“It won’t change anything,” said Ann, pounding another biscuit into the floured cloth. “Tom would never.”

I took the dough away from her and rolled it back into a ball. “I expect you’re right,” I said, keeping my eyes on my work. “Just because he’d have a place of his own, and somebody making him dinner, and waiting to warm his bed, there’s no call to think he wouldn’t want to hang around here, on the off chance that your husband will drop off to sleep.”

Ann edged me away from the table. “Go see her, Pauline. Tonight. After supper. Just pass the time with her this evening and see if you can tell what’s on her mind. She may be mixed up with somebody besides Tom.”

“Go see her?” I laughed. Ann never thought about anything but what she wanted. “Why, she lives all the way over in German’s Hill. Even if I was to stop there only long enough to say how-do and drink a cup of water, I doubt if I could make it back here by sun-up.”

Ann stamped her foot. “But I want to know what she’s up to! I can’t rest until I do. Why don’t you go tomorrow after midday and walk over there? I’ll tell James to let you.”

I thought it over. The prospect of a walk over to see my other Foster cousins was a pleasant thought for me, if the day was fine, and if I had to indulge in tale-bearing at Ann’s bidding, I reckoned it would be worth it. Besides, I was curious to see for myself how the land lay between Tom Dula and Laura Foster. I might be stingy with the truth when I got back to Ann, but I’d like to know for my own satisfaction. No use to make it easy on her, though.

“I’ll be awful tired tomorrow, Ann. You know I ain’t well to begin with. I don’t know … to make a long walk over to German’s Hill, and then to have to walk all the way back here, and get up at the crack of dawn and cook breakfast…”

Ann stuck out her lip. “I suppose I could give you a hand with the morning chores, then. But you had better find out something worth telling when you get there, Pauline. If you go over to Wilson Foster’s and spend the evening getting drunk and sleeping it off instead of talking to Laura and coming on back, I’ll take a switch to you. I swear I will.”

* * *

I got the half day off, all right. I never once heard James Melton tell his wife “no” about anything. Maybe he was scared to, but I don’t reckon he could have been worried about rat poison in his food, for I never saw Ann do that much cooking. So off I went on that next afternoon, while Melton tilled the field alone, with his two milch cows yoked to the plow. I hated to wear out shoe leather trudging through the muddy trace to German’s Hill, when I could have got there in an hour or so on horseback, but if James Melton could not afford even a scrub horse, at least he could cobble me a new pair of shoes.

The walk was p

leasant enough in the late afternoon, but I decided to stay the night, for spring nights are still bone-chilling cold, and I had no desire to make my way home on foot close to midnight in that weather, especially since this visit was being done as a favor to Ann, and I was disposed to inconvenience myself as little as possible on her account. Why is it that fine-looking folk always think they are doing you a favor by letting you do them one?

We still weren’t far enough into spring for there to be much to see on my way to the Fosters’ place—a few green leaves on trees here and there, and sprouts of grass amid the mire of rain-soaked fields. The road ran along beside the river, and it was as brown as the fields from the spring rains. I thought it looked like a trail of tobacco spit, not at all like the clear little streams we have up the mountain in Watauga County. I am not much moved by the beauty of nature anyhow, because every place I’ve ever seen looks about the same. I hoped that the Fosters would have something decent to eat and that they’d offer me some of it, and even more I hoped that there would be a full jug of whiskey and not too many people around to share it with. Whiskey is better than scenery. Better than people, too. It doesn’t ask you for anything in return.

I never paid much attention to the begats in our family, but as near as I could figure it, Wilson Foster’s daddy had been a brother to my grandfather, so we were cousins, same as I was with Ann’s mama Lotty Foster. Prosperity did not seem to run in the Wilkes County branch of the family, for Wilson was not much better off than Ann’s family. He farmed in German’s Hill, but he didn’t own the land, just worked as a tenant, so he barely cleared enough from farming to feed his family. Laura was the oldest, of an age with Ann and me, and after her came three boys and a baby girl. Their mama was dead, though, probably birthing that last child, though I hadn’t bothered to ask the particulars of it. What cooking and cleaning was done about the place fell to Laura, for there was no money to pay a servant.

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament The Unquiet Grave: A Novel

The Unquiet Grave: A Novel The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel

The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel Prayers the Devil Answers

Prayers the Devil Answers Paying the Piper

Paying the Piper The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel

The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel Highland Laddie Gone

Highland Laddie Gone The Unquiet Grave

The Unquiet Grave The Devil Amongst the Lawyers

The Devil Amongst the Lawyers The Windsor Knot

The Windsor Knot The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter

The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter MacPherson's Lament

MacPherson's Lament The Ballad of Tom Dooley

The Ballad of Tom Dooley Once Around the Track

Once Around the Track St. Dale

St. Dale Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan

Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him…

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him… Zombies of the Gene Pool

Zombies of the Gene Pool Bimbos of the Death Sun

Bimbos of the Death Sun Missing Susan

Missing Susan Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories

Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him The Ballad of Frankie Silver

The Ballad of Frankie Silver Lovely In Her Bones

Lovely In Her Bones The Rosewood Casket

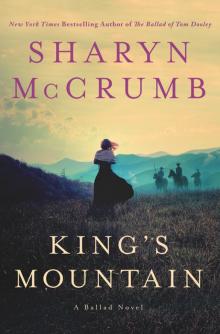

The Rosewood Casket King's Mountain

King's Mountain