- Home

- Sharyn McCrumb

The Ballad of Frankie Silver

The Ballad of Frankie Silver Read online

The Ballad of Frankie Silver

Sharyn Mccrumb

Frances Silver, a girl of 18, was charged in 1832 with murdering her husband. Lafayette Harkryder is also 18 when he is accused of murder and he is to be the first convict to die in the electric chair. Both Frances and Lafayette hid the truth. But can the miscarriages of justice be prevented?

Sharyn McCrumb

The Ballad of Frankie Silver

The fifth book in the Ballad series, 1998

THERE WERE THREE FACETS TO THE STORY

OF FRANKIE SILVER. THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

WITH THANKS TO MY GUIDES ON THOSE THREE ROADS:

Carolyn Sakowski for Morganton

Wayne Silver for Kona

Jay Brandon for 1830s criminal law

The rich never hang; only the poor and friendless.

– Perry Smith

executed in Kansas, 1965,

for the murder of the

Clutter family

The Ballad of Frankie Silver

This dreadful, dark and dismal day

Has swept my glories all away;

My sun goes down, my days are past,

And I must leave this world at last.

Oh! Lord, what will become of me?

I am condemned, you all now see;

To heaven or hell my soul must fly,

All in a moment when I die.

Judge Donnell my sentence has passed,

These prison walls I leave at last;

Nothing to cheer my drooping head

Until I’m numbered with the dead.

But Oh! That awful judge I fear,

Shall I that awful sentence hear:

“Depart, ye cursed, down to hell

And forever there to dwell.”

I know that frightful ghosts I’ll see,

Gnawing their flesh in misery;

And then and there attended be

For murder in the first degree.

Then shall I meet that mournful face,

Whose blood I spilled upon this place;

With flaming eyes to me he’ll say,

“Why did you take my life away?”

His feeble hands fell gently down,

His chattering tongue soon lost its sound,

To see his soul and body part

It strikes with terror in my heart.

I took his blooming days away,

Left him no time to God to pray;

And if sins fall upon his head,

Must I not bear them in his stead?

The jealous thought that first gave strife

To make me take my husband’s life,

For months and days I spent my time

Thinking how to commit this crime.

And on a dark and doleful night

I put the body out of sight,

With flames I tried to him consume,

But time would not admit it done.

You all see me and on me gaze,

Be careful how you spend your days;

And never commit this awful crime,

But try to serve your God in time.

My mind on solemn subjects rolls,

My little child, God bless its soul;

All you that are of Adam’s race,

Let not my faults this child disgrace.

Farewell, good people, you all now see

What my bad conduct’s brought on me;

To die of shame and disgrace

Before the world of human race.

Awful indeed to think of death,

In perfect health to lose my breath;

Farewell my friends, I bid adieu,

Vengeance on me you must now pursue.

Great God! How shall I be forgiven?

Not fit for earth, not fit for Heaven;

But little time to pray to God,

For now I try that awful road.

A rumor was prevalent in Burke County that Silver wrote some verses which were tantamount to a confession of her guilt and read them while on the scaffold to the surrounding throng just before she was executed.

The mind of Squire Waits A. Cook, a highly respected justice of the peace in the Enola section, was a veritable storehouse of legends and events of Burke County’s earlier days. He told me that the verses Frankie had allegedly written were composed by a Methodist minister whose surname was Stacy.

– Senator Sam J. Ervin, Jr.

Burke County Courthouses and Related Matters

Prologue

I WANT TO show you a grave,” the sheriff said.

Three rocks stood alone in the little mountain graveyard: smooth stubs of granite, evenly spaced about four feet apart. The stone pillars were uncarved, weathered from more than a century’s exposure to the elements and farthest away from the white steepled church in the clearing at the top of the mountain.

Tennessee deputy sheriff Spencer Arrowood wondered why Nelse Miller had made a detour up a corkscrew mountain road to stop in this country churchyard. He could see nothing out of the ordinary about the old white frame church or the surrounding array of tombstones, ranging from newly carved blocks of shining granite to older markers, tilted askew in the dark earth, scarcely readable anymore. Nearly every burying ground had stones like these.

It was pretty enough up here, Spencer allowed. The view of Celo Mountain across the valley and the blue haze of more distant peaks beyond made a fine sight on a summer morning, but Sheriff Miller wasn’t much on admiring scenery no matter how magnificent the vistas before them. He barely glanced at the view. On a hot summer day like this, Nelse was more likely to be in search of a cold drink and a shade tree, and in truth Spencer Arrowood would have preferred such a rest stop to this peculiar excursion to a little mountaintop graveyard. He was twenty-four, and impatience was pretty much a permanent state of mind for him. They could have stopped in the store in Red Hill instead of heading off up Route 80, past Bandana, North Carolina, and up another couple of elliptical miles that spiraled to nowhere. Or they could have headed back across the Tennessee line to Hamelin and got on with the day’s work. Spencer was still new enough at the post of deputy sheriff to relish every hour of duty, every moment of patrol in his shiny new ’74 Dodge. Much as he respected the old sheriff, he often found himself impatient with Nelse Miller’s unhurried serenity. The sheriff, in turn, sometimes seemed to be amused by his eager young deputy, as if he were a new puppy barking at sunbeams.

Spencer looked at his watch. Nearly noon. This old cemetery couldn’t have anything to do with business. They were still on the North Carolina side of the mountains, at the Dayton Bend in the Toe River, according to the map. Just over the state line the Toe River would change its name to the Nolichucky and the two sightseers would change into peace officers on duty instead of idlers looking at golden hills on a pleasant summer day.

Their morning’s errand had been the delivery of a fugitive to the jail in Bakersville, a little courtesy exchange between peace officers on different sides of the state line. The prisoner hadn’t been much in the way of a felon-a car thief, barely old enough to register for the draft. Since he had sobered up after a night in a Tennessee jail cell, the boy had seemed overwhelmed by the consequences of his joy ride. He had wrecked the car in a high-speed chase, and had come out bruised but otherwise uninjured. “God protects fools and drunks,” Nelse Miller declared, with some disgust.

The prisoner was handcuffed and shackled in the back of a patrol car, filthy, unshaven, and fighting back tears of panic. The two officers transporting him were not ungentle, but their lack of interest in his predicament was evident.

“What’s going to happen to me now?” the young man kept asking.

“You’re going

to the jail in Bakersville,” Nelse Miller had told him. “And after that, we’re done with you.”

They had delivered the prisoner to the Mitchell County sheriff at ten o’clock, and Sheriff Miller proceeded to spend the next hour drinking coffee and swapping stories with his North Carolina counterpart while Spencer curbed his own thirst and impatience, and smiled at the yarns as if he had not heard them a dozen times before. Finally Sheriff Miller conceded that the prisoner exchange had taken up enough of Tennessee government time. He signaled for Spencer to bring the patrol car around. Nelse Miller seldom did his own driving, a trait that bewildered his young deputy, who thought that driving a cop car was the only childhood dream that had lived up to his expectations.

As Spencer slid behind the wheel of the new Dodge, he felt his impatience slip away. He left the courthouse square of Bakersville, dutifully following Sheriff Miller’s directions, taking the twists and turns of North Carolina’s back roads, while he wondered just what the old fox was up to this time. He didn’t like to ask, though. Nelse Miller had his own way of doing things, and Spencer found that it was usually better to wait him out. Explanations would come at the proper time and place.

Now the deputy stood in the clear mountain sunshine, gazing respectfully at three slabs of quarried stone, as he waited for further enlightenment.

Finally Nelse Miller said: “I come up here when I want to remember why I came into police work. That little piece of trouble we just transported to Bakersville made me feel more like a baby-sitter than a lawman.”

Spencer looked around at the peaceful scenery, wondering why Nelse had picked this place for inspiration. He knew the Millers were from this county originally, though. “Family cemetery?” he asked, though he didn’t see any headstones marked “Miller.”

The sheriff shook his head. “These aren’t my people.” He pointed to the uncarved markers. “Charlie Silver is buried here. He was a murder victim, a hundred and fifty years back. His wife killed him. Leastways they said she did. You ever hear the story of Frankie Silver?”

“Not in detail,” said Spencer. “People mention it every now and then. It’s like Tom Dooley, isn’t it? More legend than fact. With a tune.”

The sheriff smiled. “ ‘Tom Dooley’ is a catchy folk song, I reckon, but the inspiration for it-Tom Dula-was real, all right. They hanged him over in Statesville in May of 1868, and good riddance to him. Everybody has heard about him, but they don’t know what pox-ridden trifling pond scum he was. Too bad he survived the war. Tom Dooley’s story pales beside that of Frankie Silver. I always thought it strange that not too many people outside these mountains have heard about Frankie Silver, while Tom Dooley is a household word.”

“It’s the song,” said Spencer.

“But Frankie Silver-there’s astory!” Nelse Miller pointed toward the edge of the churchyard where a thicket of bushes sloped down into a dense forest of beech and oak trees. “Eighteen years old-that’s all she was. The Silvers’ cabin was back in those woods a couple of hundred yards. That’s where it happened. The cabin was burned years ago, and the site is all overgrown now with briers and underbrush, but we could go take a look at it if you want.”

“I’m not familiar with the case,” said Spencer. “Just heard the name, that’s all.”

“My people were from up around here, so I cut my teeth on that old story. I think it’s the real reason I became a lawman. I remember as a kid hearing my granddaddy tell that tale, and wishing I could have been there to investigate the crime. I always wanted to knowwho andwhy. I still do. I thought I would solve the Silver case when I grew up. Thought if I could just learn enough about criminal investigation, I could figure out the truth.”

“Did you?” asked Spencer. “Solve it?”

“Never did. I understand some of what happened and why. But not all of it. Not that last secret that she took to her grave.”

“Maybe I’ll look into it sometime,” said Spencer. “Is there a book about the Silver case?”

“Not that I ever saw. I’ve fiddled with the notion of writing one myself, except that I’m not much on paperwork. I take a proprietary interest in Frankie Silver, though. It’s a hell of a story, Spencer. Starting right here. Starting with old Charlie Silver’s grave.”

Spencer looked at the three pillars of stone, somber in the mountain sunshine. “Well, which one is Charlie Silver’s grave?” he asked.

Nelse Miller smiled.“All of them.”

Chapter One

SHERIFF SPENCER ARROWOOD had dodged a bullet. At least in the metaphorical sense he had; that is, he did not die. Literally, he had not been lucky enough to dodge. The bullet had hit him solidly in the thorax, and had cost him his spleen, several pints of blood, and a nearly fatal bout of shock before the rescue squad managed to get him out of the hills and into the hospital in Johnson City. He had been enforcing an eviction-unwillingly, and in full sympathy with the displaced residents. The fact that he had been shot by someone he knew and had wanted to help made the attack on him that much more bitter to his family and his fellow officers, but he had not cared much about the irony of it. The injury seemed disassociated somehow from the events of that day, as if he had been drawn into another place and it did not matter much how he got there. He felt no bitterness toward his assailant, only wonder at what had happened to him. Coming so close to death had been a shock to his mind as well as his body, and its effects were so intense that it seemed pointless to consider the cause of the injury; its effect overshadowed all that went before. In the hospital he did not speak of these feelings to anyone, though. They might be mistaken for fear, or for an anxiety that might require the ministering of yet another physician. Spencer kept quiet. He wanted out of there.

That confrontation on a mountain farm had taken place three weeks earlier, and now, newly released from the Johnson City Medical Center, he was recuperating from his injuries at home.

He was able to get dressed by himself now, and to hobble around the house taking care of his own needs, microwaving what he wanted to eat, walking a bit to keep from getting stiff, and watching movies on cable until he was sick of the flickering screen. Three days earlier he had insisted that his mother go back to her own house and leave him to take care of himself. He understood that she was concerned about him, but her hovering presence had dragged him back into childhood, and he chafed at the old feelings of dependence and helplessness. He had claimed more strength and energy than he had really felt in order to convince her that he was well enough to be left alone. He had walked her to the door, waved a cheerful farewell, and then closed the door and leaned against it for ten minutes until he was strong enough to make it to a chair.

He was better now. His mother still phoned him four times a day to make sure that he was still alive, but he bore that without complaint. He knew how frightened she had been when he was shot, and how many years she had dreaded that moment. He did not begrudge her the reassurance that all was well. In fact he was determined to put an end to his convalescence as soon as he possibly could, to end her worry and his own boredom at his confinement.

He was lying in a lounge chair on his deck looking out at the valley and the mountains beyond, enjoying the spring sunshine and the ribbons of dogwood blooms across the hills, but he was still thinking about death. Physically he was recovering well, but the shock of coming so close to nonexistence had left its mark on him. Although he was past forty, he had never really thought about dying before. As a young man he’d had the youthful illusion of immortality to carry him through the daredevil stunts of adolescence and the rigors of a hitch in the army. When Spencer was eighteen, his brother Cal had been killed in Vietnam, but there had been an unreal quality about that, too: a death that occurred a world away, and a closed-casket funeral in Hamelin. The tiny part of his mind that was only ascendant in the small hours of the morning told him that Cal might not be in that box in Oakdale. To this day he might be roaming the jungles of Southeast Asia, or hanging out in bars in Saigon. Spen

cer would say that he did not believe any of this, of course, but the tiniest fraction of possibility existed, and he welcomed that doubt because it distanced him from death.

As the years went by, Spencer stayed too busy to think much about philosophical matters. Brooding on death was not a healthy pastime for someone in law enforcement. It was better to take each day as it came without anticipating trouble. Now, though, he found himself with unaccustomed time on his hands, and he was under orders to restrict his physical activity until his body had more fully recovered. He thought too much.

The sound of a car horn in the driveway stirred him from contemplation. He lurched over to the railing of the deck and looked out in time to see a white patrol car coming to a stop in front of the garage doors. Deputy sheriff Martha Ayers got out, and he waved to her, to let her know she should come out to the deck instead of going to the front door.

“Up here, Martha!”

“Figures you wouldn’t be in bed!” Martha yelled back, but she sounded cheerfully resigned to his defection from bed rest.

He tottered back to the chaise lounge and lowered himself carefully onto the canvas, allowing himself a wince of pain because Martha wasn’t close enough yet to see him grimace. She hurried up the wooden steps to the deck, pausing for a moment as she always did to admire the view. “It sure is peaceful up here.”

“I like it,” he said.

When he bought the twelve acres of ridge land a couple of years back, he had a local contractor build him a wood frame house, three stories: two bedrooms on the top floor, kitchen and living room on the middle floor, and a den, office, and laundry room on the ground floor, garage attached. Both living room and den had sliding glass doors facing the east, where the slope fell away to reveal a landscape of meadows threaded by a country road, and beyond them the wall of green mountains that marked the beginning of Mitchell County, North Carolina-out of his jurisdiction. He had painted the house barn-red, and he had built the decks himself little by little in his free time. Now they encircled the house on the ground floor and the one above, giving views from every conceivable vantage point. Spencer Arrowood liked to see a long way. The view diminished the problems of a country sheriff, because looking out at the green hills made him feel that it could be any century at all, which made his problems seem too ephemeral to fret about. Just lately, though, that same timeless quality had been showing him just how fleeting and fragmentary his own life was against the backdrop of the eternal mountains. The feeling of insignificance disturbed him. For once he was glad to have company.

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament The Unquiet Grave: A Novel

The Unquiet Grave: A Novel The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel

The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel Prayers the Devil Answers

Prayers the Devil Answers Paying the Piper

Paying the Piper The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel

The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel Highland Laddie Gone

Highland Laddie Gone The Unquiet Grave

The Unquiet Grave The Devil Amongst the Lawyers

The Devil Amongst the Lawyers The Windsor Knot

The Windsor Knot The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter

The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter MacPherson's Lament

MacPherson's Lament The Ballad of Tom Dooley

The Ballad of Tom Dooley Once Around the Track

Once Around the Track St. Dale

St. Dale Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan

Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him…

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him… Zombies of the Gene Pool

Zombies of the Gene Pool Bimbos of the Death Sun

Bimbos of the Death Sun Missing Susan

Missing Susan Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories

Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him The Ballad of Frankie Silver

The Ballad of Frankie Silver Lovely In Her Bones

Lovely In Her Bones The Rosewood Casket

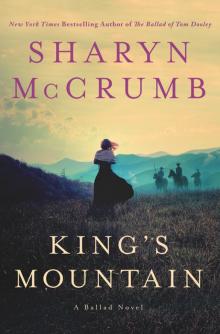

The Rosewood Casket King's Mountain

King's Mountain