- Home

- Sharyn McCrumb

St. Dale Page 5

St. Dale Read online

Page 5

“I didn’t watch the race,” the man said. “I was all set to, but I’m a plumber. Had an emergency call-frozen pipes at a mobile home. Anyhow, I left my wife home watching the race, and as I went out, I said to her, ‘Dale knows I’ll be pulling for him.’ Well, my wife can’t stand Dale Earnhardt. She says he’s a bully on wheels. Likes that California surfer boy, that Jeff Gordon. Anyhow, I’m going out the door, she yells after me, ‘I hope your old Dale gets run into the damn wall!’ And I was coming back home, hoping to catch the end of the race when I heard the news on the radio. I went on into the house, and Judy was sitting there white as a sheet. ‘I didn’t mean it,’ she says to me, but I didn’t even look at her. I just went on up into the attic and got the Christmas wreath. ‘I’m going out to the track,’ I told her, and she asked did I want her to come with me, and I said no. I didn’t want her. She isn’t hurting for Dale. But I am.”

“I’m sorry,” said Knight. That seemed to be all there was to say.

Nearby a woman in a red ski parka was crying. She held a candle that she was trying to light with a cigarette lighter, but the wind kept extinguishing the flame, making her cry all the more. “The flame has gone out,” she said. Finally, she put the unlit candle down against the wall with the wilting flowers and walked away without looking back.

“I’ll bet the Shaker Museum has a run on candles tomorrow,” said Henderson.

Bill Knight nodded.

“You know, when Princess Diana died, my wife got up at some ungodly hour before dawn to watch the funeral and I laughed at her for being so upset about it. But, by God, now I know how she felt, I guess. You feel like you knew them. It hurts.”

“And Dale never won a race here at New Hampshire,” said a heavyset older woman in the crowd. She was wearing a black-and-red Earnhardt jacket, but shivering anyhow. “He never did. Every year I’d go to the race, hoping this time would break the charm, but now it’s never going to happen.” Quietly, she began to cry.

A man in a black leather jacket and work boots stopped to look at the toy car on the Christmas wreath. He did not smile. “I wish I’d thought to bring something,” he said. “All I had in the truck was a can of beer, and that just didn’t seem right.” He pointed to one of the big rigs in the parking lot. “I got a load of Texas onions on their way to Maine,” he said. “Couple of tons of Texas sweets. And, you know what? They ain’t getting there. ’Cause I’m turning around. I can pick up I-95 outside of Boston and take it to Washington-twelve, fourteen hours. Take 66 west out of DC over to I-81 down the spine of the Blue Ridge. At Wytheville, Virginia, go south on I-77, and from there it’s a two-hour straight shot into Charlotte.”

“Charlotte?” the wreath man said.

“Charlotte.” The trucker nodded. “The funeral will be there. Bound to be.”

That made sense. Everybody knew Earnhardt was from a little town just north of there. “Do you suppose they’ll let ordinary people in?”

“Doubt it. But I can be there. Stand outside. I can say good-bye.”

“I don’t know about going to the funeral,” the wreath man said. “Drivers didn’t go to funerals. Too close to home, I guess. Knowing that the next race might be their turn.”

“Well, I’m going. The chance will never come again.”

A white Chevy pick-up truck pulled into the parking lot and the driver emerged carrying a poster portrait mounted on cardboard: Earnhardt in black-and-white coveralls leaning against his number 3 car. A gaggle of mourners helped the newcomer attach the poster to the fence above the pile of freezing flowers but some of them seemed more interested in the man who brought it than in the poster of the fallen hero.

“Vince! I thought I recognized your truck,” said one. “Are you going on to the store tonight?”

Vince shook his head. “No. I think tonight ought to be a time of mourning, that’s all.” His voice was hoarse. “I can’t open tonight.”

“But your shop is closed on Mondays.”

“No, I’ll open in the morning. I already drove over there and put a sign on the door. Nine A.M.-not a minute before.”

“You won’t mark up the Earnhardt stuff, will you, Vince?”

The man sighed and wiped his face with his hand. “No. That wouldn’t be right. Just give me time to get in and get the lights on and open the register, that’s all. Nine o’clock tomorrow. All right?”

Bill Knight, who had been listening to this exchange, said, “NASCAR souvenirs?”

Vince nodded. “It’s going to be a nightmare tomorrow. I’ve never seen people act like this. Not even when Adam died here. While I was putting the sign on the door, a couple of cars pulled into the parking lot and four guys rushed to the door, but I told them to come back tomorrow. Then a police cruiser drove up, so I went over to explain to them that I was the owner, and that it wasn’t a burglary or anything.” He sighed. “Turned out they wanted to buy Earnhardt stuff.”

Bill Knight shivered as a gust of wind bit through his overcoat. It was too cold for people to stay out here very long, he thought. He wondered where they would go, and what would become of their grief.

“I’m a minister,” he said to the shop owner. “I could open the church.”

“Most of these people wouldn’t go, sir. They need to be where Dale has been and, besides, people keep showing up all the time, and if everybody here left, there’d be no one for them to talk to, I guess. It’s better here.”

Bill Knight found himself wondering if people had gone to the cathedral on that winter day in 1170 when news of Thomas Becket’s death had reached them, and if so what had been done to comfort them.

A man in a well-cut black overcoat set a red-and-black Earnhardt hat in the pile with the other tributes. He saw the minister watching him, and gave an embarrassed shrug. “I just wanted to say good-bye,” he said.

A short man in a Rescue Squad ski parka hurried over. “Thought I recognized you, Doc!” he said to the man in the overcoat. “I’m glad you’re here. A couple of the guys have been arguing over this, and you’ll know-do you think a good trauma team could have saved him after the wreck?”

The doctor shook his head. “No. He was dead before they got him out of the car. A hundred and eighty miles an hour. We’re all just bags of water, you know. People. Just bags of water.”

As he turned to walk away, the short man crossed himself. “Well, he’s in heaven, anyhow,” he said. “I know that.”

The doctor watched him go. “In heaven,” he said. “You know, I was thinking about that on the way over here. Here’s a guy with a ninth-grade education and an average face, and by driving a Chevrolet, he gets to be the fortieth-richest person in America and hang out with movie stars-and I wondered: just what kind of a heaven would there have to be to top that?”

Knight knew that some ministers would have taken that remark as an invitation to expound upon the joys of being in the presence of God, but he couldn’t bring himself to do it. He would have felt like a salesman. Perhaps, after all, it was better to let people speak their minds, without trying to rationalize away their grief. Faith was for later.

For the next hour, until the cold wind numbed his face and forced him to leave, Bill Knight mingled with the Speedway mourners, going from person to person, saying little. Just listening to the grief and the memories.

A year later, when the Children’s Home needed someone to chaperone young Matthew on his Last Wish trip, Bill Knight volunteered, thinking that perhaps he could understand the boy’s feelings as well as anyone. Besides, he might finally learn exactly what a restrictor plate was.

Chapter V

Richard Petty in Heaven

The Volunteer Parkway

After the luggage had been stowed, a process accompanied by prolonged debates about who got carsick and who would sit where, the Number Three Pilgrims, as Harley now thought of them, allowed themselves to be herded into the bus to take their seats.

The buxom ex-beauty-queen type, whose gray hair was silvered blond,

stopped in the aisle beside the driver and called out, “Lord, I hope nobody’s taped a Bible verse to our steering wheel!”

“Shut up, Justine!” said her traveling companions in unison.

The minister, who was next to board, looked up at Harley with a puzzled frown. “Bible verse?” he said.

Harley sighed. It was starting already. Unauthorized trivia. He leaned in close and whispered, “I think she’s referring to the fact that at the 2001 Daytona Darrell Waltrip’s wife taped a Bible verse to Earnhardt’s steering wheel. It’s a Christian tradition in NASCAR.”

“Oh, yes,” Bill Knight nodded. “The race in which he died. A Bible verse to his steering wheel.” He considered this fundamentalist tradition for a moment. “I wonder which verse it was.”

Harley shrugged. “Somebody here is bound to know.” He consulted his clipboard, trying to match names and faces. He knew the minister and Matthew, the two newlyweds were joining them at Bristol…He looked up from the list, as one name gave him pause.

“Cayle Warrenby,” he said. “Cayle?”

The baby-faced blonde in black jeans raised her hand. “I get that a lot,” she said. “My mother wanted to name me Gail, but my dad was a big racing fan.”

“Well, I knew you weren’t named after the vegetable,” said Harley.

“No. My dad even called our dog Old Yeller, after that Chevy Laguna Cale was driving when he won Daytona in ’77.”

Harley smiled. “I guess you’re lucky they didn’t name you that, you being a blonde and all.” He sighed. “Cale Yarborough. Used to drive for Junior Johnson at one time. And I’ll bet old Cale was the Winston Cup champion the year you were born, right?”

She nodded. “Yes, but since he won it three years in a row, that gives me a little fudging room on my age.”

“So, where you from and all that?” asked Harley. He had written himself a note to ask that. It didn’t come naturally to him.

Cayle gestured to include her two companions. “Little towns around Charlotte, all of us,” she said. “I’m an environmental engineer, Bekasu here is a judge, and Justine is-well, she-um…this is Justine.”

A hand shot up in the air, and the tinkling of silver charm bracelets punctuated a cry of “Here I am, y’all!”

“Welcome aboard,” said Harley, who knew the type. With very little encouragement Justine would take over the bus and talk nineteen-to-the-dozen from here to Florida. She would bear watching. He glanced down the roll. “Cayle Warrenby, Justine, Rebekah Sue Holifield-”

“Hostage,” said the stern women in the white linen suit, raising her hand.

Harley wasn’t going there, either. He gave her a wary smile and said, “Okay then, who’s next? Reverend William M. Knight-”

“Bill!” said the silver-haired man who looked like he ought to be doing boomer-oriented commercials, for vitamins or mutual funds, maybe.

“And that’s young Matthew with you. Welcome aboard, guys. Mr. and Mrs. Shane McKee…Oh, no, they’re meeting us at the Speedway. I’ll tell you about them in a minute. Mr. Reeve? Mr. Franklin?”

A scowling older man in a black cowboy hat and a dark sport coat raised his hand. “Ray Reeve,” he said. “Norfolk, Nebraska. We’re not traveling together. We’re just sitting together.”

“So what do you do back there in Nebraska?” asked Harley, wishing he’d thought to take out a pen to record the answers he wouldn’t otherwise remember.

“Agro-business.” Mr. Reeve leaned back in his seat, arms folded, to indicate that the interview was over.

“Jesse Franklin,” said his pink-cheeked seatmate with a nervous smile. “Michigan. I guess you’d say I’m a native, but my folks were from down here, so I’m sure I’ll feel right at home.”

“We can provide an interpreter if you need one,” said Harley with a straight face. “And what do you do when Brooklyn, Michigan turns back into a cow pasture?”

“In non-race weeks, you mean? Ah. I guess you’d say I’m a bureaucrat. I’m the county auditor. Caught the racing bug from my uncles, though, when I was a kid. Nice to meet all you folks.”

“Welcome aboard,” said Harley. “Who’s next here…Mrs. Richard Nash?”

Midway toward the back of the bus a slender tanned arm went up, and a woman said, “Here.”

Harley looked up. That’s all she said. “Here.” She was a fine-featured woman who might have been anywhere in age between fifty and seventy, depending on whether that well-preserved handsomeness owed more to good genes or to an expensive plastic surgeon. She wasn’t wearing much jewelry or makeup, and her clothes and hair were simple enough-but Harley knew the instant he saw her that this woman had more money than God. One thing about being on the NASCAR circuit, even if you didn’t make a ton of money yourself, the social aspect of the job certainly put you in the path of people who did and, without even intending to, Harley had developed a radar for spotting power people, and this was one. How odd to find her on a down-market bus tour. He hoped she wouldn’t be the type to demand imported tea bags and linen sheets.

“Terence Palmer?” That had turned out to be the fellow beside Mrs. Nash. Her son, maybe? He looked expensive, too, but not with that patina of power that radiated from his companion. If you could bottle that air of assurance and entitlement, he thought, it would be worth more than four new tires in a five-second pit stop.

“Where are you folks from?”

The two human greyhounds looked at each other and shrugged. Sarah Nash leaned forward in her seat, but Harley was already walking down the aisle to spare her the inconvenience of shouting. “I’m from Wilkesboro, and Terence lives in Manhattan.”

“Wilkesboro!” said Harley, eyes shining. The name conjured up the good old days when NASCAR races were run in the shabby old Speedway there, the days when stock cars really were stock cars with working headlights and tires with tread. When the daddies of Dale Earnhardt and Richard Petty drove their cars to the track as well as on it. Harley wished things could have stayed that way. He’d have a better shot if they had.

“Wilkesboro,” he said again. “So do you know him?”

He didn’t have to say who. There was another famous “Junior” in NASCAR now, but in Wilkesboro, the name meant only one person, the man who invented drafting, the “Last American Hero” himself: Junior Johnson.

Sarah Nash smiled. “Yes, of course. He sends his regards.”

Harley wished they could make a detour to Wilkesboro on the tour, but even he could see that ten days to get from Bristol to Daytona and back to Darlington would be a stretch as it was without trying to improvise extra stops along the way. With a sigh of resignation, he turned back to the clipboard, to the next set of names.

“Jim and Arlene Powell?”

A white-haired older man near the back of the bus waved his hand. The woman with him was the one wearing the Earnhardt patterned vest. She did not look up at the sound of her name. Uh-oh, thought Harley. He should have paid more attention to the notes about the passengers. He hadn’t bargained on sick kids and out-of-it seniors, but at least they were race fans, so he reckoned they’d be easier to deal with than a bus full of New York media types.

“Justine…”

In the second row from the front, the platinum-haired woman with the huge dark eyes and her weight in jewelry (definitely real), waved her hand. “He-ey, Harley! Can I tell a story to get us started?”

Harley nodded for the bus driver to pull out, while he tried to think of some reason not to let her. The takeover was beginning already. She was an Earnhardt fan, all right. If you ever saw a woman at the track who looked like she ought to be following Patton into Belgium in a pastel pink tank with a rhinestone-collared poodle on the gun turret, you could bet the rent she’d be an Earnhardt fan.

“Well, let me start you off with a trivia question first,” he said, playing for time. “In fact, ma’am, you brought it up. The reverend here-”

“Bill,” said Bill Knight hastily.

“Bill wants to know

if anybody knows which Bible verse it was that Mrs. Stevie Waltrip taped onto Earnhardt’s steering column on that fateful day.”

In the silence that followed, people looked around to see if anyone was going to volunteer the information. Finally, Sarah Nash, the regal older woman sitting next to the preppy said, “It was from Proverbs. Chapter eighteen, verse ten. The name of the Lord is a strong tower: the righteous runneth into it-”

“And is safe,” said Bill, nodding. “Ah. That one.”

Justine tossed her head. “Well, what kind of idiot would tape a verse like that onto the steering wheel of somebody who was about to run the Daytona 500?” she demanded. “Talking about running into a wall-”

“A tower.”

“Whatever. That’s exactly what he did, though. Ran into something. Just like it said in the verse.” Her voice dropped to a shocked whisper. “Do y’all think she hexed him?”

“Shut up, Justine,” came two voices in unison.

“No, think about it, y’all. Who put the verse on there? Mrs. Waltrip. Okay. And who won the race that day? Mike Waltrip.”

Harley resisted the urge to put his head in his hands. Why hadn’t he thought to bring a hip flask? Or a stun gun. “The driver who won wasn’t her husband, ma’am,” he said in the firm but soothing tone one uses for people who line their hats with tin foil. “The lady is Mrs. Darrell Waltrip, ma’am. The winner of the race, Mike, is her brother-in-law.”

Justine nodded. “Even so. I ask you.” She looked around for affirmation from her fellow passengers.

“Why don’t you tell your story, now?” said Harley. Before word of this gets out and the Waltrips sue us for slander, Harley was thinking. Or tape Bible verses to our steering wheel. He pictured himself pilloried in a medieval stocks on the lawn outside DEI while NASCAR officials and Waltrip fans pelted him with ripe fruit. Stories like that wouldn’t make him any friends on the circuit, that’s for sure, and he was going to need all the friends he could get if he was going to find a way back in.

“Okay, then.” Justine tottered up to the front of the bus, her good humor restored. She waved a wrist full of bracelets at her fellow passengers. “Hey, folks!” she said. “I’m Justine, and those two over there trying to cover up their heads with their jackets are my sister Bekasu and our cousin Cayle. Now, speaking of Bible verses, I’m going to get this party going with a little story about heaven. Can I use the microphone, Harley? How do you work it?”

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament The Unquiet Grave: A Novel

The Unquiet Grave: A Novel The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel

The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel Prayers the Devil Answers

Prayers the Devil Answers Paying the Piper

Paying the Piper The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel

The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel Highland Laddie Gone

Highland Laddie Gone The Unquiet Grave

The Unquiet Grave The Devil Amongst the Lawyers

The Devil Amongst the Lawyers The Windsor Knot

The Windsor Knot The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter

The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter MacPherson's Lament

MacPherson's Lament The Ballad of Tom Dooley

The Ballad of Tom Dooley Once Around the Track

Once Around the Track St. Dale

St. Dale Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan

Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him…

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him… Zombies of the Gene Pool

Zombies of the Gene Pool Bimbos of the Death Sun

Bimbos of the Death Sun Missing Susan

Missing Susan Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories

Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him The Ballad of Frankie Silver

The Ballad of Frankie Silver Lovely In Her Bones

Lovely In Her Bones The Rosewood Casket

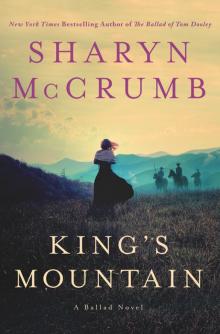

The Rosewood Casket King's Mountain

King's Mountain