- Home

- Sharyn McCrumb

St. Dale Page 3

St. Dale Read online

Page 3

“What?”

“You know-trips to the toilet.”

“Oh, sure. No problem. And, you know, that reminds me, if race car drivers go for three straight hours without ever getting out of the car, how do they-?”

Harley sighed. Sooner or later everybody asked that question. “It’s hot in a stock car,” he said. “If you sweat enough, you don’t have to pee.”

The airborne contingent of the tour, eleven people as diverse as any other group of airline passengers, wore expressions that ranged from barely contained excitement to a polite wariness that might have been shyness. The exception was one well-dressed woman who looked as if she had been brought there at gunpoint.

Justine elbowed her sister in the ribs. “Stop looking like a duchess at a cockfight!” she whispered. “There’s some perfectly nice people here. I told you there would be. Check out that hot young guy in the yellow Brooks Brothers sport shirt with the little dead sheep emblem-bet you ten bucks he’s Ivy League. And look at that distinguished fellow in the clerical collar. Oh, isn’t that sweet? He has a little boy with him. Oh, Lord, I hope they’re not on their honeymoon!”

“Shut up, Justine,” Bekasu hissed back, edging away.

Spotting their fellow tour members had been easy. Along with the tour itineraries the Bailey Tour Company had sent Winged Three caps to match the one worn by the guide and the driver. Several of the travelers had dutifully worn the headgear on the flight, in addition to various other items of Dale-bilia currently displayed about their persons: Intimidator tee shirts, sew-on patches featuring a replica of Earnhardt’s signature, and, in the case of one enterprising matron, a hip-length cotton vest featuring a montage of black Monte Carlos, made of the special Dale Earnhardt fabric sold at Wal-Mart.

There were more women than one might expect to find on a NASCAR-themed tour. At least on a tour that wasn’t dedicated to Jeff Gordon. Funny that so many women liked Earnhardt, Harley Claymore was thinking. You’d think he’d remind them of their ex-husbands. You’d think women would see Earnhardt as the weasely redneck version of the Type-A executive: the man who puts his career first, his hobbies and his buddies second, and his family a distant third. Except for all that money and fame, Earnhardt seemed to Harley an unlikely sex symbol. Wonder if he’d even managed to snag a date for the high school prom. Ah, no. Scratch that. Dale had dropped out in junior high, before the social pressures of adolescence became much of an issue. The glad-handing imperatives of his future success must have come as an unpleasant surprise for him, but he had made the transition as gracefully as he took the turns on the track. If he hadn’t, he’d have been left in the dust years ago.

Harley would like to have mused on the whole charisma aspect of the Earnhardt mystique in a group discussion on the bus, but he half suspected that the driver was under orders to report any heresies to Bailey Travel, so if he wanted his paycheck, he had better not get caught letting in daylight on the magic.

Most of the men looked like normal sports fans in a spectrum of ages, except for the preppy and the minister, who were both dutifully wearing their Winged Three caps, but with the air of generals in camouflage. And he hadn’t expected the little boy. The kid was the color of chalk, and he didn’t seem to have any eyelashes, but he seemed chipper enough. The man with him wore a priest’s collar-so probably not the boy’s father. He wondered what the story was. Harley held out his hand to the boy. “Hello, Sport,” he said. “I’m your guide. You a big Dale fan?”

The boy glanced up at his companion and received an encouraging nod. “Yep.”

Well, there was a precedent for that, thought Harley. He wondered if the sick kid was hoping for a miracle from Dale. As he recalled it had been the other way around. “How old are you, Sport?”

The kid gave him an owlish look. “Name’s Matthew. I was born the year Sterling Marlin won the Daytona 500,” he said.

Harley let out a sigh of mock exasperation. “Well, that’s no help. Sterling won in both ’94 and ’95, so I still don’t know your age.”

The kid grinned. “Okay. The first time. So, who won Daytona the year you were born?”

“Ben Hur,” said Harley. He wondered how long it would take him to match names and faces. He glanced again at his tour notes, raising a hand to indicate that a speech was forthcoming.

The tour members clustered around him and the chattering subsided.

“Tri-Cities,” he said, savoring the word. “Now you know we didn’t choose this airport just because it has a three in its name.” He’d had four months to work on his NASCAR patter for the tour and to bone up on Earnhardt connections to any place they might visit. Now he thought he could recite Earnhardt trivia without clenching his teeth. If he didn’t run out of nicotine patches, he might even survive the tour.

“Of course, this is the closest airport to the Bristol Speedway, our first stop. It was at the Bristol Motor Speedway that the young Dale Earnhardt won his first ever Winston Cup race. April 1, 1979, to be exact. Bobby Allison came in second in that race. This evening we’ll be attending the Sharpie 500 there.” To identify the race’s sponsor, Harley waved the Sharpie fine point permanent marker with which he had been taking roll. “Dale Earnhardt himself used to fly into this very airport for the race.”

For a moment everyone paused, picturing an Earnhardt wraith walking past the baggage carousel, but Harley, who had been warned not to let the tour turn into a death march, changed the subject. “Did everybody’s luggage make it? Okay, good. Then let’s get started. This is the very first Dale Earnhardt Memorial tour, and my first tour of any kind, so there ought to be a yellow stripe painted on the bumper of the bus. Just go easy on us, folks. Over there hauling your suitcases onto the baggage cart is our bus driver, Mr. Ratty Laine. I’m your guide-Harley Claymore, NASCAR driver…”

A hand waved in the air. “Do you do those hair growth commercials on television?”

“Hair growth?” Harley caught the reference. “Ah, no. That would be Derrike Cope. The way you can tell us apart is: Derrike sort of accidentally won the Daytona 500 in 1990, and I didn’t lose my hair. Hard to say which of us got the better deal.” He looked down at his notes. “Okay, speaking of Derrike, let me do a head count. We’ll get acquainted later. Right now the bus is waiting for us in the parking lot, and we have a wedding to get to.”

Justine waved her sunglasses. “I thought we were going to the Bristol Speedway.”

“Yes, ma’am, we are. The race is this evening. The Sharpie 500. After the weddings. Didn’t they put that in the brochure?”

“Heck, no. If they’d told us about a wedding, I would have brought somebody besides my sister.”

“I don’t think they’re taking volunteers, ma’am. We’re just going to watch. Oh, but two members of our party are getting married there by pre-arrangement. You’ll meet them shortly.”

“Well, if you need somebody to marry them, my sister’s a judge. Hey, Bekasu, can you marry people in Tennessee?”

While Justine scanned the crowd for her, Bekasu edged her way toward the silver-haired minister. She wanted to make allies before people figured out that she was with Justine. “Hello,” she said with an after-church smile. “I’m Rebekah Sue Holifield, and I am a hostage on this tour. How are you…Father…?”

“Just Bill,” he said quickly. “Bill Knight. I’m Episcopalian, but not that High Church.” He put his hand on the boy’s shoulder. “And this young fellow is Matthew Hinshaw, who is the real racing fan. He’s promised to help me along, because I’m new to all this.”

“Well, how do you do, Matthew,” said Bekasu, shaking his small hand. “You may have to help me along, too. I came with my sister, who is the real fan, and our cousin Cayle, who had a most extraordinary experience. She-well, never mind. Anyhow, I’m the novice in our party. To me, stock car racing looks like rush hour in Charlotte.”

“Except they’re going 180 miles an hour,” said Matthew solemnly. “And sometimes they hit each other on purpose.”

<

br /> “Matthew, why did our guide say there ought to be a yellow stripe painted on the bumper of the bus?”

The boy grinned. “That’s easy! In NASCAR rookie drivers have a yellow stripe so that people will know to cut them some slack. Hey, Bill, do you mind if I get a drink before we leave the airport? It’s time for the white pill.”

Bill Knight fished a dollar out of his pocket. “Need any help, Matthew?”

The boy shook his head and ambled away.

“Your…nephew?” asked Bekasu.

“No. Matthew lives in the children’s home affiliated with the parish. This is what he wanted to do more than anything else in the world. He’s…ill.”

Bekasu watched the little boy saunter away clutching his dollar. “Yes, I thought he must be,” she said. “I’m so sorry. Is this one of those wish tours for him?”

“Yes. He’s such a great little guy. He’s had a rough year. He lost his parents in a wreck, and a few months after that he was diagnosed with his illness. I suppose a tour is hardly enough compensation for all that tragedy, but it’s all we could do. I’m accompanying him, because the tour coincided with my vacation-not because I share his passion for NASCAR. He’s a bright little fellow, though. His doctors assure me that he’ll be all right for the duration. I worry, of course.”

“It’s an interesting choice,” said Bekasu. “He did choose this tour himself, I suppose?”

Bill Knight sighed. “Oh, yes. I think everybody was a little surprised about that, but he was adamant.”

“I’d have thought that most children would have picked Disney World,” said Bekasu.

“Matthew is an unusual boy. Very-focused. It occurred to me that perhaps an intense interest in one subject keeps him from thinking about all the things in his life that he can’t control, which is nearly everything. And I suspect that his parents were race fans, but he’s never really said. I can’t say I’d have preferred Disney World over this, but I wish I could have got him interested in my hobbyhorse, which is the medieval pilgrimages of the Church. Santiago de Compostela…Canterbury…But, I suppose a trip abroad would have been too risky for his condition. And perhaps too expensive. Anyhow, young Matthew preferred this pilgrimage. Insisted on it, in fact.”

“I didn’t know what to expect on this tour. Most tour passengers are middle-aged married couples, but I was afraid that a NASCAR tour might be a busload of drunken good old boys. This one seems to be neither.”

“Did your husband not want to come along?”

Bekasu hesitated. It was still hard to say it casually. “He died a few years ago. A few months after that Cayle got divorced, and that’s when we decided that the three of us would make a tradition of vacationing together.”

“That sounds like fun.”

“It has its moments. But I didn’t bargain for a racing tour. What about you? Are you from-” Bekasu cast about for a city associated with racing. “Umm-Indianapolis?”

“Rural New Hampshire. Our town is just north of Concord, about eight miles from the New Hampshire International Speedway. It’s called Canterbury, so you can imagine my delight when I was posted there, but, much to my chagrin, I have since discovered that Thomas Becket takes a backseat to Ricky Craven there. I keep trying, though. Slide shows, lectures at church functions. To no avail-racing fever is rampant. Still, the drivers are very good about coming to the Children’s Home and signing photos for the kids. One of them played Santa Claus for us a few years ago, they tell me. I’m new to the parish, so I’m still getting used to all this. I didn’t really know much about Earnhardt until the day he died.”

“I think we’re being rounded up,” said Bekasu, glancing back at the cluster of travelers. “And here comes Matthew with his drink.”

Cayle appeared beside them. “You’d better come on, Bekasu. Justine is asking whether they have a P.A. system on the bus, and I’m pretty sure she’s going to try to sing Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Earnhardt…”

Bill Knight laughed. “Must be a Southern hymn,” he said. “Not in our hymnal in New Hampshire.”

“Excuse me while I go and rain on my sister’s parade,” said Bekasu.

Chapter IV

The Knight’s Tale

February 18, 2001

Some time that week, he could not remember exactly when, Bill Knight had seen a shooting star flame out against New England’s winter sky. He recalled thinking, as he always did at such a time, The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes. You could hardly call it a premonition. Still, he never quite forgot it.

That Sunday morning several big-screen TV owners in his congregation had invited him to Daytona Parties, the Super Bowl of NASCAR they called it, but he had begged off, saying he had paperwork to do. Instead, he promised them that he would watch the race by himself while he worked. An easy promise to keep, since he usually did turn the television on for noise while he wrote.

He was looking forward to a relaxing evening alone with his slides and lecture notes: pilgrimages in the medieval Church, an erudite and obscure pursuit that had long afforded him a retreat from all things modern and confusing, like church sound systems and word processing software. He hoped to work up a lecture on the pilgrimage of Santiago de Compostela, and so he told himself that the bookish evening might indeed be considered “work” or at least the preparation for work. He would skip the Daytona parties with a clear conscience but, in deference to local customs, he knew that he must not skip the race itself. It was a restrictor plate race-whatever that meant.

The culture of stock car racing took some getting used to for someone who had heretofore believed that any major sport must end in the word “ball.” When Knight had first arrived, so many people asked him to remember 19-year-old Adam Petty in his prayers that he had looked up the name in the church directory to see which of the boy’s relatives belonged to his congregation. Finally, someone explained to him that Adam Petty had been a novice driver, NASCAR royalty-the grandson of Richard Petty himself-who had been killed in a wreck at New Hampshire International Speedway that summer. People grieved for this famous stranger, killed in race practice in their vicinity, much as they would have mourned a local high school quarterback killed on I-93. For Bill Knight, it was a mindset that he was still trying to master.

With barely a glance at the race already well under way, he had settled in behind his desk with an NHIS coffee mug (a legacy from the parsonage cupboard) and a stack of note cards and photographs. He thought about muting the sound of the race so that he could concentrate on his work without distraction, but he decided that this would not be quite in keeping with his promise to watch the event, so he left it on. Later, he came to think of this decision-or indecision-as a sign that some higher authority than his parishioners had meant for him to watch this race, but he never shared this pious thought with anyone. His flock of New Hampshire Protestants might believe in messages from heaven as a general principle, but they frowned upon modern-day citizens-particularly their own clergymen-claiming to receive them. As befitted their Puritan ancestry, his congregation preferred a faith of austere simplicity, one in which visions and prophecies were as suspect as incense.

A native of western Maryland, Bill Knight was still charmed by the Christmas-card prettiness of the countryside, and of Canterbury itself with its colonial homes, its village green, and the Shaker Museum, all a few miles north of Concord, off I-93, and-as if in apposition to all this colonial simplicity-one exit away from the New Hampshire International Speedway. Loudon, as the track was usually called for the sake of brevity, after the town closest to it, was a major regional attraction, bringing in tourist dollars and turning traffic into a nightmare one weekend each July and September. Then 50,000 people converged on the area for the NASCAR Winston Cup races. He soon realized that the sport would affect him whether he followed it or not, just as residents of Wimbledon or St. Andrews cannot be indifferent to tennis or golf.

On the whole, he was pleased with the area and with the cadence of life in

New England. Less than a hundred miles from the amenities of Boston, but well out of the city sprawl and traffic-he had the best of both worlds. No one had objected to a divorced pastor, and none of the unattached women in the congregation had made any strenuous efforts to change his marital status. He found the people kindhearted, but a bit shy with newcomers, and he was still finding his footing with the local customs. When people asked if he found New Hampshire to be very different from Maryland, he would smile and say, “Colder, but I’ll get used to that.” He resolved to learn how to ski, for his own pleasure and for winter exercise, and to take an interest in stock car racing as a gesture of goodwill toward his congregation.

For the next hour or so, he sifted through photographs of churches in southern France and Spain. He kept encountering himself in various seasons and outfits, standing, hands in pockets, trying to look earnest as he posed squinting in the sunshine in Ardilliers or holding up a souvenir of St. Martin in Tours. There were well-composed photos of church architecture in which he stood in the foreground for perspective, but he was still tempted to remove those shots from the collection. He kept staring at the image of his old self, knowing that he had been looking at Emely. There were no photographs of her in the pilgrimage program. He had been careful to remove them, so that he would not come across them unprepared and be blindsided by the memory. Emely was gone, and he had gotten over it.

He worked on his notes, scarcely glancing at the television screen as the rainbow of race cars streaked past. He paid little heed to them beyond thinking that the sight of a balmy day in Florida made a pleasant contrast to the New England winter evening fading to black outside his window.

As he wrote, with half an ear tuned in to the rhythmic voices of the announcers, newly-familiar names like “Waltrip,” “Labonte,” and “Bodine” slid past. And Ricky Craven, of course. Craven, who was from Maine, was a favorite son on the New Hampshire track. Occasionally Bill Knight glanced at the screen, but the blur of cars told him nothing about the progress of the race. With the cars racing in an oval, you couldn’t tell who was winning by which car seemed ahead of the rest: it might be on a different lap from the others, and the race consisted of 200 laps. Hours and hours of going round in circles. Much like a church council meeting, he thought to himself.

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament The Unquiet Grave: A Novel

The Unquiet Grave: A Novel The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel

The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel Prayers the Devil Answers

Prayers the Devil Answers Paying the Piper

Paying the Piper The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel

The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel Highland Laddie Gone

Highland Laddie Gone The Unquiet Grave

The Unquiet Grave The Devil Amongst the Lawyers

The Devil Amongst the Lawyers The Windsor Knot

The Windsor Knot The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter

The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter MacPherson's Lament

MacPherson's Lament The Ballad of Tom Dooley

The Ballad of Tom Dooley Once Around the Track

Once Around the Track St. Dale

St. Dale Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan

Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him…

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him… Zombies of the Gene Pool

Zombies of the Gene Pool Bimbos of the Death Sun

Bimbos of the Death Sun Missing Susan

Missing Susan Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories

Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him The Ballad of Frankie Silver

The Ballad of Frankie Silver Lovely In Her Bones

Lovely In Her Bones The Rosewood Casket

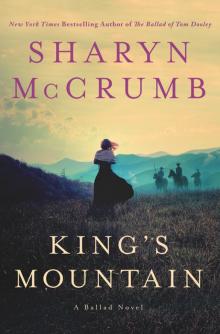

The Rosewood Casket King's Mountain

King's Mountain