- Home

- Sharyn McCrumb

The Devil Amongst the Lawyers Page 2

The Devil Amongst the Lawyers Read online

Page 2

The old reporter set a couple of nickels next to his coffee cup, and blew his nose on a paper napkin. “This job may not make you rich, boy,” he gasped out between coughs, “but there’s not much more power to be had in this world than that of a newspaperman, if you know how to use it.” He began to roll another cigarette. “When the Lord cast Adam and Eve out of Eden, he posted an angel with a flaming sword there to guard the gates. Well, sometimes I feel like that angel. I wield that flaming sword against all mankind at my discretion. Hell, son, the pen isn’t mightier than the sword. It is the sword.”

The front door opened bringing in a blast of cold air, and, with a few more valedictory wheezes, the reporter passed through it and was gone. For a long time after that, Carl sat at the table staring at nothing, and thinking about pens, and angels, and the sad dark eyes of Mary.

ONE

NARROW ROAD TO A FAR PROVINCE

Each day is a journey, and the journey itself home.

—MATSUO BASH

Two hours west of Washington, Henry Jernigan finally gave up on his book. This Mr. John Fox, Jr., might have been a brilliant author—although personally he doubted it—but the clattering of the train shook the page so much that he found himself reading the same tiresome line over and over until his head began to ache. The November chill seemed to seep through the sides of the railroad car, and even in his leather gloves and overcoat, he did not feel warm.

He thought of taking a fortifying nip of brandy from the silver flask secreted in his coat pocket, but he was afraid of depleting his supply, when he was by no means sure that he could obtain another bottle in the benighted place that was his destination. Prohibition had been repealed eighteen months ago, but he had heard that some of these backwoods places still banned liquor by local ordinance. He repressed a shudder. Imagine trying to live in such a place, sober.

A man lay dead in some one-horse town in the mountains of southwest Virginia. Well, what of it?

The only thing that made death interesting was the details.

In point of fact, the death of a stranger no longer interested Henry Jernigan at all. In all his years on the job he had seen too many permutations of death to take much of an interest anymore, but even if the emotion was lacking, the skill to recount it was still there in force. Jernigan would supply the telling particulars of the story; his readers could furnish the tears. All that really mattered to him these days was a decent dinner, a clean and quiet place to sleep, and a flask of spirits to insulate him from the tedium of it all.

He brushed a speck of cigar ash from the sleeve of his black wool coat. Henry Jernigan may have been sent to the back of beyond by an unfeeling philistine editor, but by god that didn’t mean he had to go there looking like a yokel. True, his starched linen shirt was sweaty and rumpled from the vicissitudes of a crowded winter train ride, and his shoes, hand-stitched leather from a cobbler in Baltimore, glistened with mud and coal grit, but he fancied that the essential worth of his wardrobe, and thus of himself, would shine through the shabbiness of the suit and the dust of the road. Henry Jernigan was a gentleman. A gentleman of the press, perhaps, but still a gentleman.

He looked without favor at the book in his lap, and with a sigh he closed it, marking his place only because he was reading Fox’s novel for research, not for pleasure. After sixty interminable pages he had begun to think of the book as “The Trail of the Loathsome Pine,” a quip he planned to spring on his colleagues as soon as he met up with them. At last winter’s trial in New Jersey, clever but ugly Rose Hanelon had made a similar play on words with a Gene Stratton Porter title. When the family governess had committed suicide, Rose took to referring to her as the “Girl of the Lindbergh-Lost.”

No doubt Rose was on her way here, as well. He thought of going to look for her on his way to the dining car when it was closer to dinnertime. At least one need not lack for civilized conversation, even in the hinterlands.

He knew all the big wheels on the major papers, of course. The places changed, but the faces and the greasy diner food stayed the same, no matter where they went. He didn’t see those smug jackals from the New York Journal American, though. That was odd. The word was that the Hearst syndicate had paid for an exclusive on this trial, so he had expected to see their people. Either they had already arrived, or they had what they needed and went home, relying on local stringers to send them the facts of the trial.

Henry’s paper seemed ready to fight them for dominance of the story, though. They had even assigned one of the World Telegram photographers to accompany him to this godforsaken place.

Rose Hanelon of the Herald Tribune would be here, though. Henry was fond of Rose. While technically she was a competitor, they got along well, and he flattered himself that his serious readers and the sentimental followers of her sob sister columns were worlds apart, so that, in fact, no rivalry existed. He even looked the other way when Rose slipped Shade Baker a few bucks to take photos for her, too.

The brotherhood of the Fourth Estate: it was as close to a family as Henry had these days. He went back to thinking up clever epigrams to entertain Shade and Rose at dinner.

They never printed their heartless little jests, of course. Mustn’t disillusion their readers, who saw them as omnipotent and benevolent deities meddling in the affairs of mortals. At least, Henry liked to think his readers imagined him in such an exalted position, if only for a few fleeting hours before they wrapped the potato peels in his newspaper column, or set it down on the kitchen floor for the new puppy. Sic transit gloria mundi.

The train clattered on, and he stared out at the barren fields edged by a forest of skeletal trees. In just such a landscape, the broken body of a child had been unearthed.

Now that had been a story. A golden-haired baby kidnapped . . . Father a dashing pilot, who gained worldwide celebrity as the first man to fly nonstop across the Atlantic . . . Mother an ambassador’s daughter . . . Frantic searches . . . Ransom demands, and then all hopes dashed when the child’s remains were found in nearby woods in a shallow grave . . . that story had everything. Wealth, culture, celebrity, tragedy, and since it had all happened in New Jersey, a comfortable distance from Washington and New York, the reporters had been able to make excursions back to the city.

That had been the perfect assignment. All of them thought so. A case that transfixed the world, enough drama and glamour to sell a year’s worth of newspapers, all set in a civilized locale convenient for the national press. And for a grand finale: the execution of the guilty man, a foreigner—a detested German—who had been caught with the ransom money hidden in his garage. If they had invented the tale out of whole cloth, they couldn’t have done better.

In this case they wouldn’t be so lucky. This time a backwoods coal miner had got his head bashed in, and because the culprit—or the defendant, anyhow—was a beautiful, educated girl, the newspaper editors thought that Mr. and Mrs. America would eat it up. Provided, of course, it was served to them in a palatable stew of sex, drama, and exotic local color. Henry Jernigan was just the chef to concoct this tasty dish.

He directed his gaze out the window, hoping to soothe the pain in his temples with the calming effect of the austere view: more brown, empty fields, bare hillsides of leafless trees, and beyond that the distant haze of blue mountains, indistinguishable from the lowlying clouds at the horizon.

In the stubbled ruin of a cornfield, he saw a ragged scarecrow swaying in the wind, which summoned to mind a favorite verse from the Japanese poet Bash: “A weathered skeleton in windswept fields of memory . . .” He looked around at his fellow passengers, bundled up in drab clothes, sleeping or staring off into space. Surely he was the only person present conversant with the works of Bash. Yes, once Henry Jernigan had possessed a soul above the cheap pratings of a tabloid newspaper, and in his cups he still could quote from memory the masters of literature from Li Po to Cervantes. But what good had it done him?

Scarecrows in dead land.

The chiaroscuro

vista sweeping past him only succeeded in further quelling his spirits. Jernigan hoped he liked the countryside as much as the next man, but as a city-dweller born and bred, he preferred nature in cultivated moderation: a nice arboretum, for example. This temperate jungle spread out before him, tangled underbrush and dense forest, hedged by dark, forbidding mountains, simply reinforced his belief that he was leaving civilization. At least, he was leaving single malt scotch and the Paris-trained chefs of Manhattan’s restaurants, which amounted to the same thing.

It was the fault of Mr. John Fox, Jr., that he was on this journey in the first place—all the more reason to loathe the man’s book. Still, he would persevere, hoping that if he kept reading, the text might provide him with a few wisps of atmosphere to spice up the story he would have to write. The book, first published in 1908 and popular again now only because of the film currently being made of it, took place in the 1890s, but surely nothing had changed around here in the ensuing four decades. Besides, where else could you turn for a primer on the backwoods culture of the Southern mountains? He needed some telling details, a few quaint folk customs, some strands of irony to elevate the sordid little tale to the level of tragedy.

Details were Henry Jernigan’s specialty. Well, all of their specialties, really. Each of his colleagues-cum-rivals, all of whom were probably holed up somewhere on this interminable train, had his own forte in transforming an ordinary account of human vice and folly into an epic saga that would sell newspapers. Jernigan’s own skill lay in framing an incident in the classical perspective, so that every jilted lover was a thwarted Romeo, every murdered wife a Desdemona. He regaled his readers with his cultural observations, making allusions to historical parallels and literary counterparts, working in a telling quote to elevate the tone of even the most sordid little murder. Highbrow stuff, so that the readers could tell themselves they weren’t wallowing in the squalor of poverty and misery; they were gaining a new perspective on the essential truths of classical literature.

He was lucky to work for a newspaper that could afford such literary extravagance. Some of his colleagues had to stagger along on blood and gore accounts not far removed from the True Detective pulps, and the sob sisters had to manufacture a beautiful and innocent heroine in every dung heap of a case they covered. He had heard that there were reporters who could do the job cold sober, but he wouldn’t like to try it.

His gaze returned to the infernal book on his lap, The Trail of the Lonesome Pine. Absolute hokum and melodrama: Harvard engineer romances pure mountain gal against the backdrop of a feud. Its author had much to answer for. Of course, except for the geographic location, the novel was not even remotely connected to the death in question, but if Fox’s book had not existed, Henry Jernigan would be back in New York or Washington, enjoying a leisurely dinner in convivial company, instead of hurtling through the Virginia outback along with the rest of the carrion squad.

Bring out your dead, he thought. The phrase was apt. It made him think, not of plague corpses on London carts, but of the influenza victims in the Philadelphia of his youth. He shuddered, and pushed away the image. He and his colleagues scavenged not on carrion, but on the hearts of the victims: the loved ones of the slain; the family of the accused; and all the peripheral little souls whose lives were besmirched by the crime of the moment.

He was so pleased with the erudition of this observation that he looked around the car for some fellow sufferer to share it with, but the only other colleague he recognized was his assigned photographer, Shade Baker, slouched down in a window seat, with his hat over his eyes. Pity. Epigrams would be wasted on him. Baker was a son of the Midwestern prairie, an artist of blood and bone, using his artistry to illuminate the bruises, the blood-stained bodies, and the pathetic artifacts of the crime scene.

Last year Shade’s photos had illustrated the lurid stories that had waxed poetic over the battered body of little Charlie Lindbergh, unearthed from that shallow grave in the Jersey woods, so heartbreakingly close to the house from which he was taken. The Lindbergh case was the last time they had all been together.

Elsewhere, Luster Swann, whose gutter press tabloid made Henry shudder, was probably chatting up the most angelic-looking girl on the train, wherever she was. Swann, a gaunt bloodhound of a man, was invariably drawn to vacant-eyed blondes who looked as if they had just wandered out of the choir loft. The irony was that there was no greater misogynist than Luster Swann, who thought all women either treacherous or wanton, or occasionally both. He seemed always to hope to find some ethereal innocent who would convince him otherwise, but he never succeeded, which was just as well, because his journalistic specialty was a judicious mixture of cynicism and righteous indignation. To Swann every female defendant was a scheming Jezebel, and every weeping victim a little tramp who deserved whatever she got.

Jernigan scanned the car one more time, but no familiar faces gazed back at him. None of the others were around, but they might turn up later on in the dining car.

Oh God, he needed a drink.

“BE YOU HEADED for Knoxville?”

Jernigan started out of a daze as if the book itself had spoken, but when he turned in the direction of the voice, he found that his seatmate, the rabbity man in the rumpled brown suit, who had snored most of the way from Washington, had now awakened, bright-eyed and in a talkative mood.

Jernigan shook his head. “Knoxville? No, not as far as that.” He forced himself to respond in kind. “How about yourself, sir?”

“Oh, I’m going up home to Wise. Been to see my sister and her family up in the big city.” The little man looked at him appraisingly, taking note of Jernigan’s well-cut suit and the gold clasp on his silk rep tie. A slow grin spread across his face. “Coal company business, then? Like as not you’ll be headed up to Wise County, I reckon, to visit the mines.”

Jernigan inclined his head. “My business does take me to Wise County. Would you be a resident there yourself?”

“Born and bred,” said the man happily. “I’m not in the mines, though, no sir. My business is timber. I hope you’ve made arrangements for accommodations in the town already. Lodging should be at a premium this week.”

“In a village in the back of beyond?” Henry’s murmur conveyed polite skepticism. “Why should it be crowded, especially at this bleak time of year?”

The man blinked at him, astounded by this display of ignorance. “Not crowded?” he spluttered. “Did you not hear about the murder trial that’s about to start up there?”

Henry Jernigan was careful to set his face into a mask of polite boredom. “Why, no,” he said with as much indifference as he could muster. “A murder trial, you say? I don’t suppose it amounts to much, but if you’d care to pass the time, you may tell me something about it.”

Had he identified himself as a reporter and attempted to question this garrulous stranger about the local scandal, no doubt the man would have clammed up and refused to utter a single word on the subject, but by implying that this singular news was of no consequence to him, he had ensured that he would be regaled with every salacious detail the fellow could muster. Odd creatures, human beings, but entirely predictable, once you had learned the patterns of behavior. He contrived to look suitably indifferent to the tale.

“A man got murdered up there in Wise County back in the summer,” his seatmate declared.

Jernigan stifled a yawn. “Nobody important, I daresay?”

“Well, sir, it happened in Pound, which is barely big enough to be called a village, so everybody there is somebody, if you catch my drift. Anyhow, it wasn’t no ordinary killing, no sir.”

“Gunned down by some feuding neighbor, I suppose? Or felled in a drunken brawl?” said Jernigan. He opened his book again.

“Now that’s just where you’re wrong,” said his seatmate, eager to be the bearer of scandalous news. “You’ll scarcely credit it, but they went and arrested the fellow’s wife and daughter for the crime. They let Mrs. Morton go right away, decided

not to prosecute her, but they charged the daughter with first-degree murder. Yes, sir, they did. And her the prettiest little thing you ever did see, and ladylike, to boot. Been to college and then came back and taught school up home. Last girl in the world you’d expect to do a thing like that. Last . . . girl . . . in . . . the . . . world.”

“Pretty, you say,” said Jernigan, raising his eyebrows with polite disbelief. “And by that I suppose you mean ‘passably attractive for a village maiden.’ Fine blond hair, good teeth, but perhaps she has the face of an amiable sheep, and the overstuffed body of a dray horse? Ankles like birch trees?”

“Now that’s just where you’re wrong, sir,” said the man, who felt that being the authority on this local sensation made him temporarily equal to this superior-looking gentleman. “Pretty, I said, sir, and pretty I meant. Miss Erma Morton is a slip of a girl, dark-haired with big brown eyes, more doe than dray horse. Just twenty-one years old. She has a quiet, ladylike way about her, too. She could be in the pictures, I’m telling you for a fact.”

So the accused was a beauty. Henry Jernigan relaxed a little, relieved to have the early descriptions of the accused confirmed in person by a local source. Stories about pretty girls in trouble practically wrote themselves.

“Indeed?” he said. “But why would a lovely and learned young woman such as you describe resort to the killing of her own father? The poor creature was deranged, I suppose.” He coughed discreetly and lowered his voice. “I have heard it said that venereal disease can—”

The little man was shocked. “Why, no such thing! There was no trouble of that kind, I assure you, and I’ve known her all her life.”

“Friend of the family, are you?” said Jernigan, scenting blood.

“No, I wouldn’t go as far as that, but we knew her to speak to, same as anybody would. There are no strangers thereabouts. And she was always a good girl. Now I don’t say the young lady didn’t have a mind of her own, going off and getting educated like she did, and maybe her father was apt to forget that she was a grown girl paying rent to live there. They say he wanted to lay down the law like he did when she was a little girl. Curfews and such.”

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament

Elizabeth MacPherson 07 - MacPherson’s Lament The Unquiet Grave: A Novel

The Unquiet Grave: A Novel The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel

The PMS Outlaws: An Elizabeth MacPherson Novel Prayers the Devil Answers

Prayers the Devil Answers Paying the Piper

Paying the Piper The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel

The Ballad of Tom Dooley: A Ballad Novel Highland Laddie Gone

Highland Laddie Gone The Unquiet Grave

The Unquiet Grave The Devil Amongst the Lawyers

The Devil Amongst the Lawyers The Windsor Knot

The Windsor Knot The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter

The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter MacPherson's Lament

MacPherson's Lament The Ballad of Tom Dooley

The Ballad of Tom Dooley Once Around the Track

Once Around the Track St. Dale

St. Dale Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan

Elizabeth MacPherson 06 - Missing Susan If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him…

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him… Zombies of the Gene Pool

Zombies of the Gene Pool Bimbos of the Death Sun

Bimbos of the Death Sun Missing Susan

Missing Susan Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories

Foggy Mountain Breakdown and Other Stories If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him

If I'd Killed Him When I Met Him The Ballad of Frankie Silver

The Ballad of Frankie Silver Lovely In Her Bones

Lovely In Her Bones The Rosewood Casket

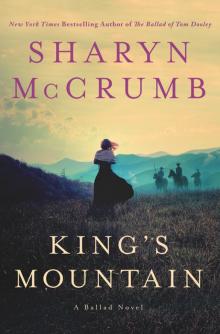

The Rosewood Casket King's Mountain

King's Mountain